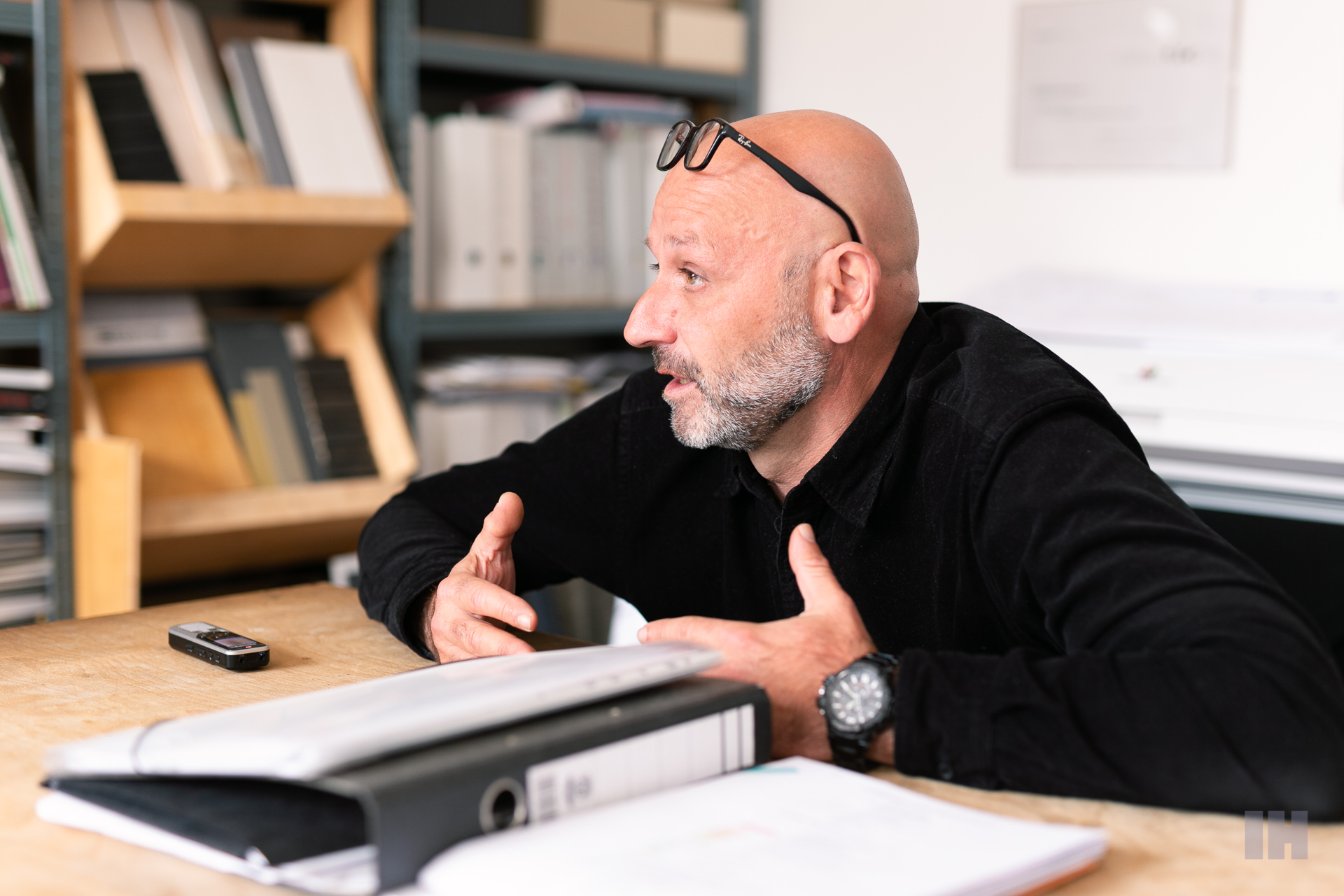

Every building is a living organism. It is important to respect its values and social benefits, says architect Irakli Eristavi from the zerozero studio

Although he was born in Tbilisi, he has lived in Prešov since the age of four. Architect Irakli Eristavi from the zerozero studio together with his team stands behind the designs of several buildings, awarded architectural prizes such as CE ZA AR, ARCH and the Dušan Jurkovič Award. One of the most famous reconstructions he participated at is the restoration of Košice’s Kasárne/Kulturpark during the city’s title of European Capital of Culture 2013. In the following interview, Irakli comments on the attitude to transforming abandoned buildings into their new forms while considering the values of public construction.

You often transform unused old buildings into spaces for new use and form. What does this process mean to you? Especially if your project is later used to mediate culture?

The profession of architects is definitely a challenging one. It is largely about the responsibility to the environment and social connotations that result from the object. It’s not just about the visual side, or simply the “nice design”. Every architectural work begins with an evaluation of the situation, an understanding of the context – this phase sometimes becomes a sort of torture for many. It is necessary to understand the environment of the building in wider interfaces, as well as its economic or social aspects. The big difference in these aspects is played by the fact whether it is a building for the private or public sector.

The public contracts for the zerozero studio were the famous Kasárne/Kulturpark, Námestie Centrum in Prešov and a pedestrian cycle bridge over the Poprad River. In this case, one considers the consequences of one’s decisions, rationalizes all points of view. If the project is conducted through a public tender, it has advantages for architects in the freedom of choice for design. There is no discussion as to what the proposal should be, as the concept of the winning proposal has already been approved. The private sector is more inclined to influence what the final construction will look like.

However, what is important to me and to the entire team of our studio is the long-term sustainability of the project – we stand for the fact that things – either buildings, objects, works or paintings – should last and serve people. An essential part is the teamwork of several architects. Today, architecture is no longer the field of one genius who works steadfastly alone. Likewise, the whole job requires consistent management. Last but not least, all those involved in the design must keep in mind that the construction needs to last not only from a technical but also from a moral point of view. We are always very pleased if we have the opportunity to create a space for the cultural segment. It is a very motivating work and we have a close relationship with it, as in the case of ViolaPrešov.

How do you feel about seeing the final face of Kasárne/Kulturpark and you know that this project is the result of a zerozero design? What is it like to look at such a big puzzle in its current form?

The Kasárne/Kulturpark project is the result of the activities and dedication of several people. Sitting there is a really pleasant feeling, even though I can’t get rid of the reflection in my head of the whole process – all the struggles, changes, unexpected situations. I sit there and see us wading through the mud in Wellington boots before the pavement was laid. The construction phase itself brought a great deal of stress with it. We received dozens of questions every day – there were occasional mistakes in the project, we found things we didn’t expect or which we didn’t even dream about on the premises of the century-old military barracks. This adrenaline sport lasted for about a year. Every day we went from Prešov to Košice, sometimes even twice. Opposite the construction, we rented an office with a view of the complex and the construction site.

The construction of a new project cannot even be compared to reconstruction. You need to be able to handle those unforeseen situations and deal with them. It must have taken a part of our lives, when I recall those days. On the other hand, I feel proud of how we managed to put together a great team of people who participated in it and brought it to a successful end. The inaccessible area fenced by a wall has become a cultural icon of Košice. I am especially pleased to this day with the potential of the square, which we have added to the park. Today, it is home to the skate community and I always wander there when I’m in town. That square definitely brought me the strongest joy of the whole project.

“When looking at the completed projects, it’s nice to see the features of what the architect imagined in the first designs. However, one must face the truth – things sometimes do tend to get out of control. The building is a living organism and absolutely depends on the involvement and cooperation of other people.”

In the case of the Kasárne/Kulturpark project, you also considered the moral aspect of the complex – in your opinion, there could have been no question of ruining the site. What’s your stand of the moral side of architects when interfering with old buildings and public space in general?

It is primarily a matter of respecting the values created by generations of people before us. It is often related to the political period of the particular country – for example, architecture from the times of socialism is often perceived as something ugly, concrete, functionalist. At the same time, the idea of what is nice and what is not is simply subjective. That is why it is important to build awareness of what those values truly are, and I mean not just in architecture. It is sometimes difficult to make people understand concepts or materials if they have no knowledge of this subject. Currently, a great example is the new TV series Icons, broadcast on RTVS.

Kasárne/Kulturpark were a very specific case in this respect – as the Regional Monuments Office failed to register the complex at the given time in the Central Register of National Cultural Monuments in Slovakia, it freed our hands and the city also. This shortened the time of processing, negotiating the project and subsequent permitting of the construction. Nevertheless, we consulted the proposal and the whole process with various conservationists. We respected the value of the original building that was there. It should be noted that these were not barracks with a crew, but supply barracks of the Austro-Hungarian army, with warehouses and a bakery. As the existing buildings showed high architectural quality, we wanted to preserve as much as possible.

How do you feel about development projects in the city and their relationship to urban planning? How do you think they affect the functioning of the city?

I have to admit – in the almost twenty years that we have been operating as a studio, we have flirted with this idea several times. However, we have never been able to fully satisfy developer customers in their idea of the yield of the environment and the visuality they prefer. However, it is appropriate to say that developers are different, and we can find big differences between them. Focusing on profit is not necessarily a bad thing, capitalism is a reality of our era. The other side of the coin is the social benefit of the design – the very fact that unused space is transformed and someone pours life into it again is clearly beneficial. Nevertheless, the benefits that these interventions should bring vary. The degree of improvement in the social situation and the environment is something that should be assessed in the long term and consistently before the intervention. When the profit is higher than the social benefit, scepticism arises.

Where are you from? Why do you live in this country and not somewhere else, why here and not in the capital? Is your origin related to the profession of architecture and the creation of projects for Prešov and the surrounding cities?

I was born in Tbilisi, my mother of Slovak and father of Georgian origin. We lived in Tbilisi until I was four, then we moved to Slovakia. Later I studied in Bratislava and after graduation, I had the opportunity to live in Berlin, London and Rotterdam. The milestone was returning from Berlin to eastern Slovakia. In fact, I did not tend to move to Bratislava, I felt that my home was really here. I do not think that all architects, designers, and the like, should be concentrated in the capital. It is necessary for them to remain scattered in the country and to contribute to the improvement of the environment through their activities. We are also doing this specifically in this region, where I have my roots. When a person creates something in the space where he comes from, he/she feels that he/she may be repaying his/her debt in some way. It is simply a different emotional bond, difficult to explain with words.

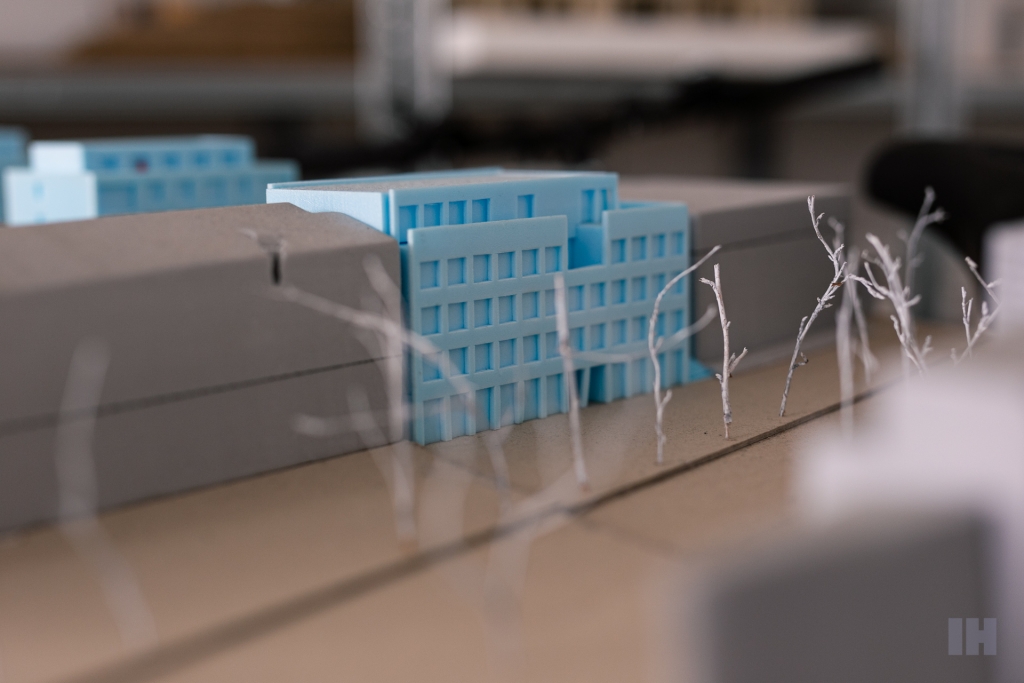

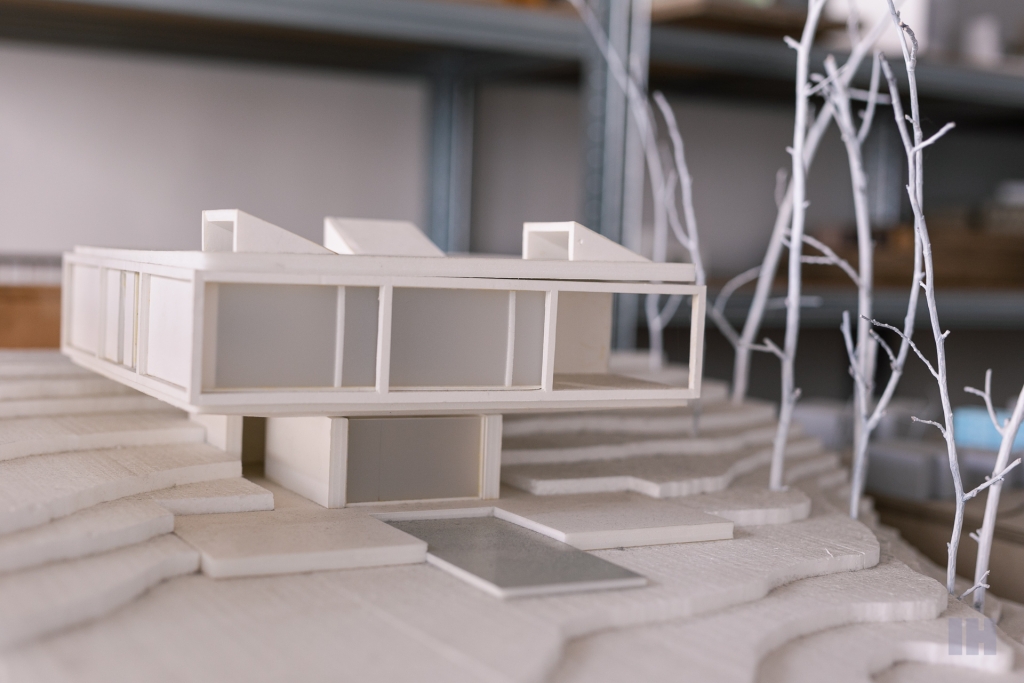

The project of the Town Hall House in Leopoldov

What are you currently working on? Which of your projects do you cherish most and like to reflect back to?

The construction of the Town Hall House in Leopoldov is currently underway, for which we won a competition in 2014. It is another project close to our hearts, as it is a public building, such as the Kasárne/Kulturpark project. The Leopold Town Hall House has a long and significant history and means a lot to the local people. This is also evidenced by the fact that they announced a nationwide competition/tender for this reconstruction. Sometimes it takes years to see the final project – the whole process can also be called a long-distance run.

This is also a serious task due to the type of contract. During the first Czechoslovak Republic, public and official buildings were given considerable importance in the form of spatial, material and architectural quality. Later tendencies and constructions of the ‘90s ceased to show an adequate standard for these buildings. After a long time, therefore, there is an effort to renew this tradition and comment on what we, zerozero architects, think the representation of public administration should look like. It is also probably my favourite project together with the Sulín cycle bridge over the Poprad River, where we encountered very interesting challenges. It was a matter of proposing the bridging of the river, in the centre of beautiful but raw nature, moreover in the context of the merger of two independent states belonging to the European Union.

Last year, we also won a competition in Prešov for the revitalization of Kmeťovo stromoradie (Kmeť tree alley). It’s the design of a new pedestrian promenade under the chestnut trees, which have been located here for more than 100 years and run parallel to the entire centre. The tasks associated with cultural infrastructure and public space are something that we are personally very interested in and which we naturally want to participate in the most.

Do you think that education about how we perceive public space should be introduced? How do you feel about the impact of architecture on a person, and thus the environment in which people live? Where to start with responsibility?

In my opinion, it is a matter of education and the quality of our education. It is well known that the teaching profession has long been underestimated, as it is in other sectors. The values of education and cultural and historical awareness were pushed to the periphery in the pursuit of material possessions and experience. It is necessary to raise awareness about architecture, art and culture in general from the youngest generations in schools. There they begin to become acquainted with the relevant connotations, which they can apply in every sphere to which they go.

Invisible Mag is supported using public funding by Slovak Arts Council. The Slovak Arts Council is the main partner of the project.