Community is the driver of change in society. Ján Gálik talks about active citizenship and the connection between activism and art

We talked with Ján Gálik about squatting in Košice, the strengths and weaknesses of communities, but also about what does it feel like to organize the biggest protests since 1989 and what is the current message of the initiative For a Decent Slovakia.

We met at the Lower Gate, where it all started. Half-empty Main street was in contrast with my memories of the overcrowded squares and times where thousands of people stood in rain and cold weather to bring alive the message of Ján Kuciak and Martina Kušnírová. One can talk about anything with Ján – from culture, activism, art, and what it means to be an active citizen or what dramaturgical methods he has brought to Tabačka Kulturfabrik from his activity in the squat club called KLUB. We stopped at the cult graffiti of a baby and an older man depicted on the gate of the former squat place during our walk. What are the past and future of activism in Košice?

Punk is politics

“Ever since I was a child, I was fascinated by things that are at the fringe of society and are in defiance of the general opinions. Even though I am not a punk prototype, I was interested in this subculture. As I get older and wiser, I don’t see punk the same way I did in the past. It is not about fashion, eccentric behavior, or visible resistance. I see it more via optics of antifascism, solidarity with those in need, and fighting not against society but people threatening the weaker ones. Maybe I don’t have such intense contact with the current scene, but I try to go to concerts and exhibitions and overview how the punk scene works now. KLUB was really helpful in that.

Today’s punk is more mature as opposed to when we were teenagers. The scene is richer. The magazines are published, and there are activism exhibitions. People have an overview of the socio-political situation in Slovakia and abroad, and they react to it. Indeed they still have piercings and tattoos, but it is more than that. I have noticed conflicts among an old and new generation of punks where the new generation claims punk to be politics, and I incline to that view.

Every activity that forms the world can be called a political act. Especially in punk, which was formed from the resistance of the working-class, so on-demand to change the politics, point out the injustice, and manifest dissatisfaction sometimes in the extreme, unusual or unconventional ways. Punk has always been a political opinion for me.“

Club called KLUB

“I had few reasons to establish KLUB. I have always dreamed of having a squat, so I was kind of selfishly fulfilling a dream of mine to have an abandoned house where I can do things that matter. Squatting comes from the philosophy that is opposed to overconsumption. We live in a world of extreme differences. There are many rich and famous people and people who can’t afford to buy basic things for a living. KLUB was also about social justice. We tried to distribute the excess we had to those who needed them. We did clothes or food donations, as an example.

Squatting applies the same idea to buildings. Many of them are not used, and at the same time, many homeless people are living on the streets. There are also more radical squatters – they squat a building and then offer it to people in need. But that’s not how we wanted to do it, as squatting doesn’t have a long track of history and tradition here and therefore is not that well known. It would have caused a lot of misunderstanding.

We tried hard not to present the scene as violent and radical but to spread the core values of squatting. We chose the form accordingly to be understood by people.

I also had other reasons to start the squat. KLUB was established just after Košice became the European Capital of Culture. This title has brought many positives as well as negatives. As I get older, I can see that the positive things outnumbered the negative ones, but I saw it differently back when I established KLUB (laughter).

I had a feeling that everyone is interested in culture only when paid for it. There used to be few active individuals, and suddenly we had tens of cultural managers and hundreds of civic associations in Košice. Many projects were created only as a reaction to the grant scheme. Most of them were working only when they got the funds. I doubted their sincere interest in culture.

I wanted to create a space that works without any grant scheme. An area that works only thanks to passionate people and the need for self-realization. KLUB was a space where you didn’t have to fill in any documentation and go through all the bureaucracy. It was a place where people could experiment and organize events without fear of failing. There would be no reprisals or need to give back the money received from grants.

However, the boldest reason was that cultural centers are not only places to represent art and consume culture for me. I see them as a space where an engaged, active community interested in the world around, helping to create it together, can emerge. I think there are many things we should react to, whether the segregation of the Roma community or problems of violence against the LGBT+ community. That was the essential element of activism for me in the process of creating a cultural and community center.“

Kindergarten of culture and activism

“My main goal in KLUB, Tabačka or other projects as well is based on the principles of helping others to gain independence. It feels good to prepare an exhibition or a concert for people. But it is even better to motivate them to organize it themselves. It has always been more valuable for me when young people emerged and tried to organize a discussion than organizing the events myself. In one way, the center was supposed to be an incubator of community organizers.

I see culture inseparably linked to activism and solidarity, in connection to floods or the explosion of the block of flats in Prešov, for example. In these situations, spontaneity, speed, and flexibility are what matter the most. We can see the state is ossified, and everything takes too long to happen, even if there is a good intention. On the other hand, smaller non-profit organizations can execute their ideas immediately. We saw it during the pandemic as well – all kinds of organizations from the non-profit sector got together and were able to supply face masks to medical stuff even months before the first ones from the state arrived.“

City is built of communities

“Every country consists of people. Of course, an individual has some word in society, but when people group, they can change a lot more. Community is the driver of changes in society, city, town, state, or even a national park.

Community organizers are precious people who connect individuals with their common goals. If a whole community demands a change, it is of greater importance for the institutions or the surrounding. There is a saying that if one person dances, he must be crazy, but when two people dance, they can get other people to join them, and their dance becomes powerful. From this point of view, it is crucial to have that other person joining you.

I am glad that communities became the point of interest for people from European and state institutions in the past few years. To have communities is an essential element of a healthy civil society. Communities can be beneficial for the state, as they can define their own needs and consequently comment on the state’s intentions. They can also collect data that the state is not able to do. If the state decides to listen to its communities, they can become a gift for it.

Since the closure of KLUB, I work in Tabačka as a community and music dramaturg, and I take care of the active citizenship program. We try to offer people space to self-realize, become more active, and come with their own culture and community events. Such said we want it to be a space for them to grow, learn and build their self-confidence. It was quite challenging during the times of Corona, but it was possible. There are people who want to do good things in Košice – they only need trust and a safe space.“

Corona was a hard time for all communities, but it remarkably hit the Roma one

“Physical contact cannot be substituted by anything else. Corona was hard for every community, but we all kept in touch in the online space at least. Thanks to the active base we had, many projects, some of them very successful, came to life.

Many of the restrictions didn’t make sense for marginalized Roma groups; let’s say “staying at home” or “washing your hands for five minutes” as examples. There is no access to running water in some settlements, or they can’t afford to stay at home during the lockdown, as they need to get wood from the forest to keep their children warm. I was pleasantly surprised that the communities I came in touch with were taking things seriously. We often communicated about their kids and school, what tests they currently need or how long it is valid. Unfortunately, the state closed off many of these settlements and thus approached Romas as second-class citizens. It was a particular situation for them also with education. You need to have a computer, internet, and electricity to join distance learning. We collected around thirty notebooks and distributed them to families, which we were sure would not sell them but use for actual learning. Our state failed here, and I even had an experience that the Roma community was many times more disciplined than some of my friends.

I have to say, there is always hope for Roma people. It is a great misfortune we keep helping them from the outside and try to think about how they should function as a community. We have just recently started to allocate responsibilities and trust to local people who live there, have respect, and local inhabitants believe them. The project Omama is an excellent example of good practice. If we continue in this way, I think the situation in communities must improve.

It took hours of work to organize protests For a Decent Slovakia

In the beginning, there were four of us in the initiative For a Decent Slovakia in Košice. We asked one of them to leave the initiative almost immediately, as he was active in one political group. It was important for the initiative to be apolitical. Interestingly, everyone in a group favored a different political party, which might prove we were not politically motivated.

I was not supposed to be the spokesman of the initiative in Košice. My main contribution was that I had experience with event organizing. People say that the best arguments come to your mind in the shower at home, but once you get in front of the camera, your brain gets stuck, and you can’t express yourself adequately. I was the one who could do it the best, and that’s why I became the spokesman.

For a Decent Slovakia was very spontaneous in terms of protest, but there was an enormous workload around it. I even lost my job because of it. We spent from seventeen to eighteen hours a day on the preparations. Daily, we discussed things around the speakers, media, graphics, sound technicians but also less visible things like electric cords, tea, thermos, city’s permission, etc. At the same time, we were in contact with the families of Ján and Martina and with forty other organizations from all over Slovakia, with whom we tried to coordinate our activities. Every day there were some changes. We watched every press conference. I learned a lot about how politics and its control institutions work and the roles and competencies of the Constitutional Court, the Senate, or Slovak Police Force president.

When talking only about the protests, there was a massive wave of dissatisfaction among people. But it was not us who created it; we only tried to direct it in a more cultivated and decent way for protests to be peaceful. The most important was to give everyone in the protest a chance to identify with some of the speakers. Dramaturgy was put together in a way for people to realize that we need to lead by the example of decent and cultivated speech as it is the only way to change our country.

We deliberately chose the speakers to represent people of all ages, genders, or religious preferences. Many people approached us and wished to speak out during the protest, but sometimes it was not possible. From time to time, we felt we could help, such as when we connected angry farmers with Andrej Bán, and it initiated separate farm protests. There were thousands of messages and e-mails coming. I still keep a table with hundreds of contacts.

We were putting together the dramaturgy for smaller cities as well. We also needed speakers to approach those people so that big protests would not only be in Bratislava, Banská Bystrica, or Košice. We never told anyone whom to vote. We traveled the whole country, and we tried to motivate people to vote. But as I have already mentioned, For a Decent Slovakia protests had always been an apolitical movement in a way we never let anyone from politics be a speaker. We allowed Andrej Kiska to sing the national anthem of Slovakia, but that’s it. I remember my voice shaking when I called the Office of the President, but I told them we didn’t wish for the mister president to have a speech.

Many people criticize us for not enforcing some political party during the protests. We had gatherings in fifty cities in Slovakia, thirty more of them abroad. There were thousands of speeches, but none told people whom to vote for in the elections.

We didn’t campaign for any political party during the municipal, European, presidential, or parliamentary elections. On the other hand, we tried to do campaigns for social mobilization where we were publishing newspapers and traveling around the country. We visited some villages that politicians forgot for over thirty years, and that’s why people felt lonely. We encouraged them to vote. We asked them if they know elections are coming, if they vote regularly, or understand the Europarliament’s influence on life in Slovakia. But eventually, it was us who listened most of the time. It is easy to spread some nice slogans from Košice, Bratislava or Banská Bystrica, but when you come to villages like Nová Sedlica or Jelšava, the reality is entirely different. You need to know the actual situation in the whole of Slovakia to organize protests we did or to comment on the current situation. It was a very enriching experience, and we got to know lots of fascinating people. It gave us hope that situation in Slovakia is not that bad as it might seem.

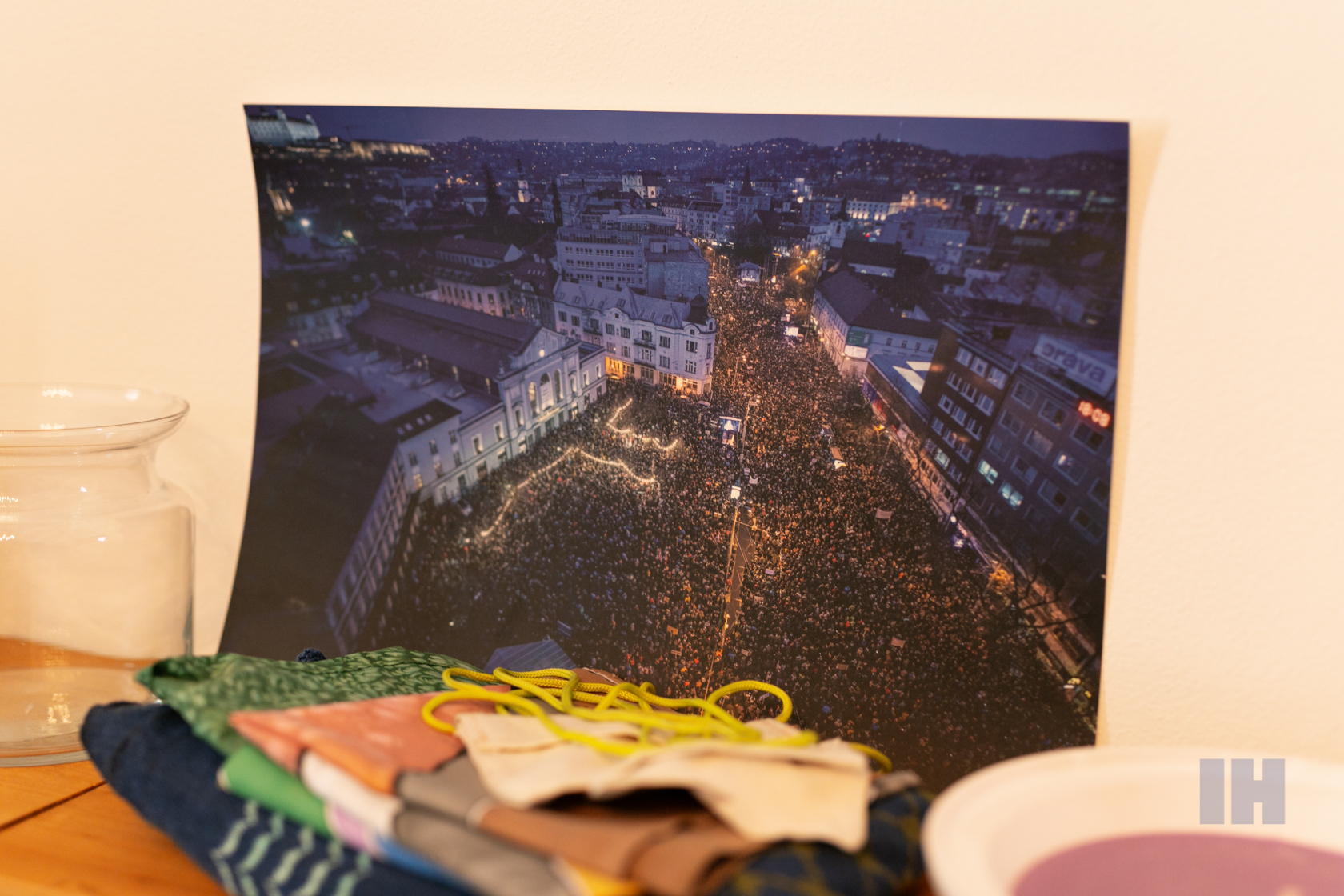

For a Decent Slovakia has brought a lot to Slovakia and Košice as well. It is mainly an awareness that many people care about freedom and are willing to fight for it on the squares peacefully. They become invisible in times of criticism, hate, and online fights on Facebook. When you look at social media, you feel that our society is completely divided, but most decent people do not take part in it. That’s the reason we tend to forget they exist. But the truth is they are the majority as opposed to two extreme groups that fight among each other all the time. I think the protest provided us with an understanding that there is a considerable number of us.

That’s the reason I think For a Decent Slovakia initiative was successful. Unfortunately, the enthusiasm faded away soon after the new government was elected. Before the elections, society had expected decency and maturity to arise, but that is not exactly what happened, as we see. And it could look like the initiative was not successful because of that. But as I have mentioned before, we never told anyone for whom they should vote. We chose this government, and therefore it is what we deserve.

During the protests, we often came back to the main reasons for doing it all –Ján and Martina. We didn’t want their lives and message to become just some electoral campaign. It would be inhuman and unacceptable for us. If we did so, we definitely wouldn’t gain and deserve the trust of all the people that came to the protests. It would be a sign of disrespect towards those people as well. I believe the initiative’s message and contribution of For a Decent Slovakia will appear in a few years, even if it looks like we’ve just got out of the frying pan into the fire now. I believe that the memory of solidarity, culture, and decency we saw will be written into our minds and manifest later on in the future.

Movie about a Decent Slovakia

Originally, I am a photographer and a movie-maker, but since I have been mostly focused on event organizing in the last few years, this part of my work is not visible. My intention for a movie about a Decent Slovakia is to capture what the movement meant for the organizers. I want to depict our train of thought, describe processes, how we were deciding, or the dilemmas, challenges, and conflicts we had to face.

I want to do it now, while it’s still fresh in our memories. I am afraid that if we talk about it in thirty years, everyone’s version will be different. It is logical because everyone has their view of reality, and every truth is genuine and honest for them. But I think that all those truths are evaluated differently after some time compared to living them in real-time. Now we have all that it takes to evaluate which steps were reasonable and which weren’t.

It is crucial to keep the records of testimonies while people still remember. It is equally important to capture testimonies of Ján and Martina now so that later on, they are not misused by some populists and their narrative of foreign agents trying to make the country fall apart. They might also talk about us being LGBT+ progressive movement or oppositely extreme conservatives and homophobes. There should exist records of people who were personally there so that the others watching it as time passes can confront the stories and fairytales about the initiative For a Decent Slovakia with authentic testimonies.“