He escaped from communist Czechoslovakia and lived in the USA for 50 years – Ján Gadžo

How can one have three different lives? Or recognize the limits of materialism and have enough, rebel restlessly against oppression or recover from the traumas of the past regime? Ján Gadžo from Strážske in Eastern Slovakia knows these answers – his family, kulaks, lost their property, harvest and dignity during the process of collectivization. Ján’s persistent resistance to communism in former Czechoslovakia resulted in an escape from his native country to the West, where he worked hard in several professions and fulfilled the so-called American Dream. What were the lives of Ján Gadžo during communism, in capitalist America and current democratic Slovakia like?

Persecution of kulaks

His grandparents Frajkors met and got married in Pittsburgh, the USA in 1900. Later, they returned to Strážske near Humenné, Slovakia. Here, their daughter Anna settled with her future husband Andrej Gadžo. Their family, as their name in the Eastern Slovak dialect suggests (gadžo – rich or the one of great wealth), owned 17 hectares of land. However, their wealth, frequent visits by family members from across the Atlantic, and American clothing caused a general feeling of being frowned upon, accompanied by ridicule and humiliation. The persecution took a strong turn during the collectivization process of the communist regime when small and medium-sized farmers were voluntarily or forcibly made to sign the confiscation of their property to collectively-controlled and state-controlled farms, as Ján himself describes.

“In 1952, they began to build the Chemko enterprise in Strážske. At that moment, they had already taken about 5 hectares from us, for which they paid us some money – at least that’s what my mother said. My father invested this money and quickly bought agricultural tools and machines – however, it was not very useful to us since the Communists continued to persecute my parents because of our land. We did not want to give up our lands. From an early age, I felt this strong aversion, hatred towards communism. At school, we were told lies about the evil capitalist West, but from what I had seen, my uncle from America brought us bags of clothes every year. I rebelled and argued with the teachers and they always gave me bad marks for my behaviour. More than the education, I was interested in reacting truthfully to the situation around me. I wanted to study geography, political science. However, my mother convinced me that I would not make a living and I entered the Secondary Industrial School of Electrical Engineering in Prešov. Although I didn’t like the school, these were no times to choose a school on my own.”

Sign or get in a car

The 1950s brought further persecution of the family and the Communists gradually took away all their crops from the harvest. Consequently, there were times when the family had nothing to eat and starved. As a result of such an intervention to human needs, Ján enjoys good food and doesn’t look at prices when on grocery shopping: “To this day, I spend a lot of money on food – sometimes I don’t even care about how much I pay. It’s a consequence of what I experienced as a child. At first, they took our crops, then the cattle, and finally the land. In 1959, a car arrived at our yard. My mother was given a choice – she had to either sign the documents by which our land was to become the property of the collective farms or get on a truck. How many people know about such measures today? I will never forget how I walked home from school and heard the radio playing a celebratory song for signing the documents to my parents, ‘comrades’. I ran home, even though I was telling myself it couldn’t be true until the very last minute. But it was true – they forced them.”

After taking the land, Ján’s parents were employed in the new municipal enterprise, Chemko. He mentions the 1960s and the Prague Spring as a period that flourished in culture, dance, music and a distinguished and educated nation, to which Alexander Dubček himself gave democratic hopes. Since Ján argued more than studied at school, he began to work closely with the local Macedonians, who had been doing business and selling ice cream in Strážske for many years. It was, therefore, outside of school where he received his education in the field, which he used many years later: “Although they built a new school building, a football pitch and the conditions were generally better thanks to the town’s enterprise, I could not get over the fact how delusional and deceptive the regime was. The school lost its interest for me – Macedonian merchants taught me the craft and also the languages. This helped me a lot later, I quickly learned Polish, Russian, German, English and even Spanish. I considered the Slovaks as a well-educated nation and I never had to sweep the floors or do any other less favoured job when I fled to America.”

The Communists found me in the mountains

“Ever since I remember, I have always known that I would have to flee my home country. During high school studies in Prešov, I started to travel around Czechoslovakia. I worked on a farm and I did not want to return home to the East. Strážske didn’t mean much to me at that point anymore – I only returned when my mother had her leg amputated after a car accident. I wandered with my friends around the country, I even worked as a mountain carrier in the High Tatras. Yet, the Communists found me even in the mountains – at that time I realized that playing with the openly negative attitude towards the regime could have gone fatal for me.

I was only sixteen when I came up with a plan for my friends and me to go to Yugoslavia and to flee to Austria from there. However, I did not succeed in escaping until 1969, six months after the occupation by Russian troops took place in Czechoslovakia. I moved from Belgrade to Maribor and I crossed the border at night only with my personal documents, money and a pair of clean socks. Afterwards, I spent almost half a year in the Traiskirchen refugee camp before I managed to fly to America to meet with my uncle.”

“I can’t explain what the Communists did to the people. Nevertheless, my life went the way I wanted it to. The young generation should remember what we went through so that it is not forgotten – and so it does not repeat.”

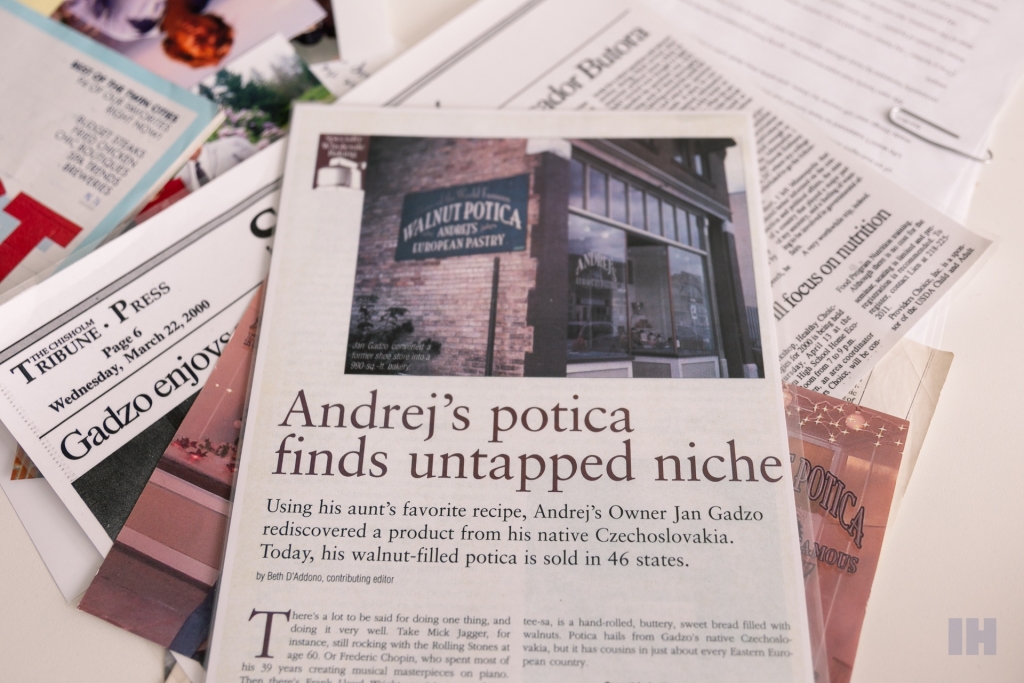

Andrej’s European strudels

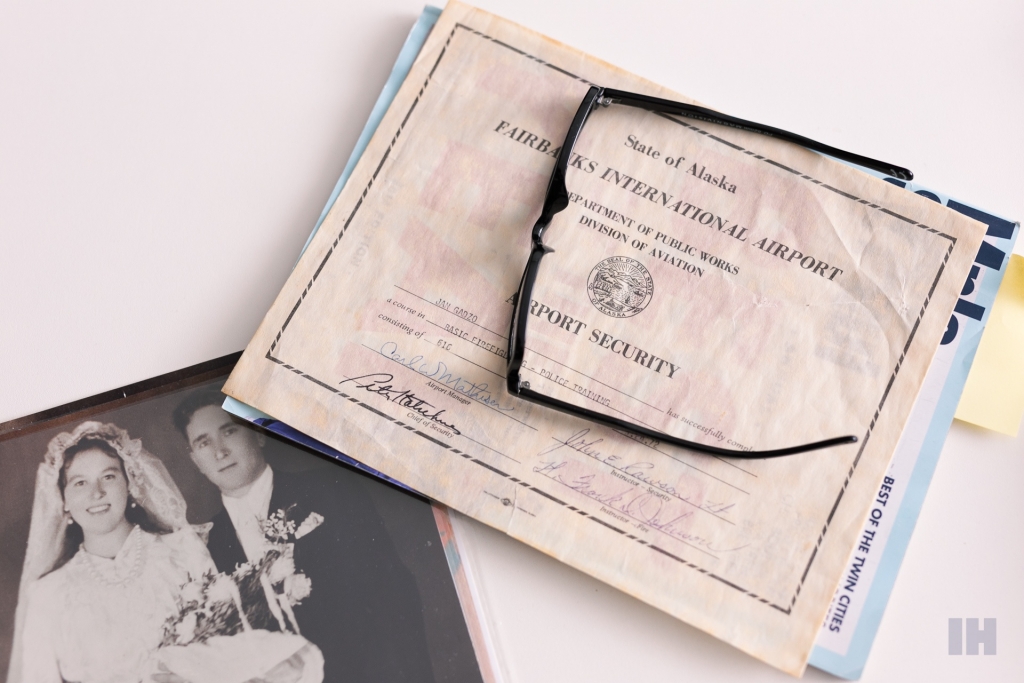

After fleeing to America, Ján’s fate led to various directions and professions. He himself calls this 50-year stage the “second” of three lives he has had. He claims that in the 1970s, in a foreign capitalist country full of immigrants, he had to try twice as hard than the locals to become successful. During the Vietnam War, he worked at the Alaskan base, Fort Wainwright, where he reached the level E4 from E1 in mere seven months. A soldier usually accomplishes such a rank only after serving for several years. Ján often links his future achievements to his own competitive character or tenacity, which he acquired at an early age back home.

“I was promoted in the Army forces, even before I was an American citizen. It was a war, I knew how to run fast and aim well – that was enough to upgrade me to E4. I remember how horrified the soldiers returning to us from Vietnam looked. It was terrible to see them in that way, yet their own Americans looked at them with disgust. After the war, I worked for a company that sold ventilation machines and I travelled across the United States. In 1978, I married my wife Jean and settled in Minnesota, where we raised our only son, Andrej, whom we named after my father. The year 2000 was a turning point in our careers – we built a network of bakeries with traditional walnut and poppy potica/strudels under the label Andrej’s European Pastry. We had 12 employees and we prepared and delivered 20,000 pieces of strudels a year. We also worked as part of catering service during Václav Havel’s visit to Minnesota.”

Return to home

It took 21 years for Ján and his family and friends from Slovakia to reunite again, it happened after the revolution, in 1990. Despite the new democratic regime, he was extremely afraid to go back home – while his train was approaching the Czechoslovak border, he feared that he would jump out of the window. The return to Strážske was a great success, though – the family and people he had not seen in over two decades waited for his arrival at the railway station. Ján continued to visit Slovakia more frequently during the post-revolutionary period until he finally decided to return permanently in 2019.

“One day, while looking at the high snow in front of my house in Minnesota, I said to myself – that’s enough. I wanted to come back and I even told my wife I would leave with or without her. But we came back together. Today we live next to the New Hospital in Košice. I like this city – I can travel from here comfortably and quickly to the High Tatras, where I worked and roamed around when I was young. The city offers me a space to relax and focus on culture, art. That’s something I deserved after all these years. And so I began to live my third life here.”

We bring regular stories about interesting and inspiring people. Meet Košice’s personalities and book a room in the design rooms of The Invisible Hotel.