If you have the desire to do something creative with other people, you find each other

We met Laurie Vestøl, the founder of Urban Space Lab online. It looked like a very improbable meeting because we have written few mails to e-mail addresses, provided to us by Arts Norway Council during our partner search. Contacting unknown people in a foreign country with the proposal to submit a project didn’t guarantee a positive outcome. We have got one response. It was a perfect match for the future Slovak-Norwegian cultural matching project. After the main activities of the projects were over, we sat down with Laurie to ask her a few questions.

So let’s introduce Urban space lab. What is the aim of the project? Why did you find it? Please tell us about the main projects that you are working on now.

OK, thank you yes. Well, I worked as a landscape architect for 25 years and then as a city planner in Skien for 8 years where artists and citizens participated in reusing an old brick city. But the funding was difficult, and the bureaucracy was frustrating. The master plan for the city lacked plausible implementation strategies for public green space. So, I founded Urban Space Lab in 2017 in order to do something more ecologically meaningful. The freedom to work as an environmental artist allows me to focus on reconnecting people to nature. I build upon a stable foundation that doesn’t switch according to the whims of wealthy developers.

Contemporary art is a form of communication that stimulates through the senses. I love working with tactile resonance- exploring what it means to be a human today and using imagination and symbolism. The shrinking of nature in our collective imagination and our cultural conversation is most likely due to a lack of time outdoors. So maybe we can connect communities to nature and get back into touch with organic materials.

I would like to talk with you about the word lab. You have it in the title of your company, and we use these words very often in our work, especially in the field of creative industries. So what does it mean for you? What does it mean in your work?

Yeah, I think that’s an interesting question because there’s so many people that use the word lab in different ways. For me, it’s just about exploring a place together. Involving users in site exploration makes sense since they have grassroot knowledge. Having an interdisciplinary team of professionals and artists running the labs is also important for the quality of the results. If it’s just a one-time event I call it a workshop. But if I use the word lab, it’s usually a series of explorations happening over a longer period of time. Lastly, labs must be innovative and interdisciplinary. You’re not just doing the same thing that’s been done before, but rather opening up to new ideas and new people. You know, connecting the sustainability of the place to a sense of belonging. In a deeper way, the process of co-creating is interesting. The collaborative process maximizes shared value.

If you sit in a place for days, years, hours, whatever…you become connected to the site. But if somebody else comes along, they experience it differently and have other ideas. So I’ve defined different types of labs depending on the different approaches and problems that need to be solved. For example, with social labs, it’s societal problems like poverty, health, or racism. Living labs are about the environment, such as the destruction of resources or the need to create green parks and gardens. I like to organize Art Labs to develop cultural programs or build experimental art installations.

You were talking about labs and interdisciplinary collaborations. So what does it mean for you when you use the word interdisciplinary? What are the disciplines you would collaborate with?

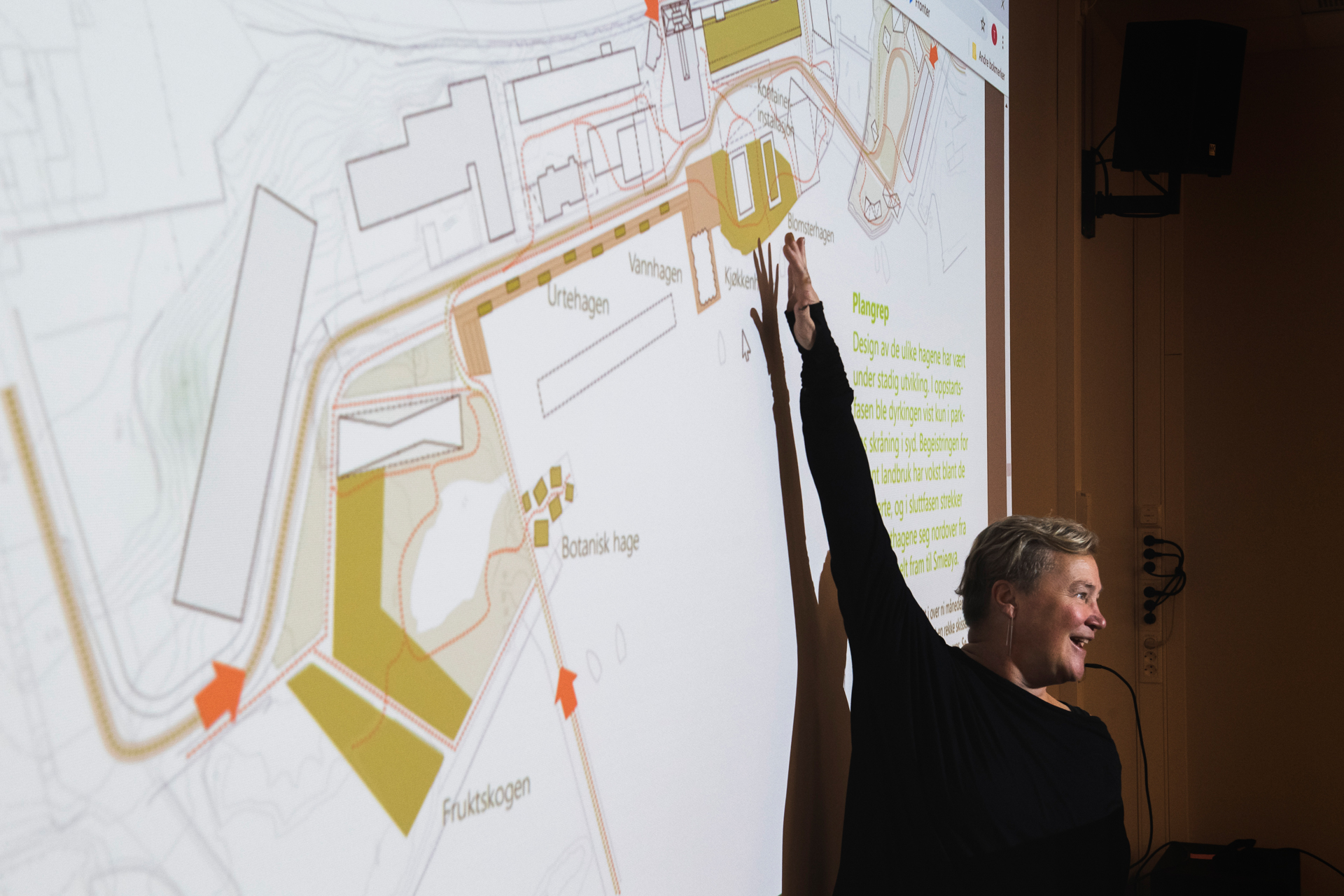

That’s a good question. It depends on the site actually, because I think the place is very decisive in terms of how I organize the labs. The first factor is who owns the property, whether it’s a public space or whether it’s privately owned. In this example, the polluted empty industrial site was going to be transformed into a public park but was owned by a private owner. So, I involved the neighboring high school and science teachers in the labs- due to the sustainability aspect. Then I involved five different researchers. One is an expert in women’s rights and medieval history- since the plot used to be the site of Norway’s first medieval Abbey. The history of these amazing women has totally disappeared from the city. The nuns were there for 400 years, so I thought that was a very interesting aspect. Next, we involved soil researchers because the land had been an industrial site for 100 years. Environmental consultants could tell us what kind of pollutants were in the ground, and help the kids take soil samples without getting contaminated. The safety of the students also became a discussion about climate change, fear, and hope for the future. Lastly, I involved 4 professors of paper making. The site was an abandoned paper factory, so we made handmade paper in a sustainable way from plants on site – such as nettles and grasses. The nuns made handmade paper, so we kind of went back to the Middle Ages for our inspiration. A botany professor took us on plant safaris around the island to find the seeds descended from the plants used by the Abbey. So that’s just one example where we involved maybe 100-300 people within a three-year period. Urban farming, composting, fungi culture, and growing fruit forests- then there were the Art labs with glassmaking and spiritual Health Labs with the neighboring drug rehabilitation center.

Uh, you’re talking about very specific and interesting projects? How do you find inspiration? How do you find them? Or do they find you?

They find me. I think when you’re open to doing meaningful projects in the world, the meaningful projects find you. Especially if money isn’t the primary motivation. If you have the desire to do something creative with other people, you find each other. Also, I’m in a different phase of life than a lot of younger people and can spend the last years of my career giving something good to the world – trying to protect and caretake nature.

Let’s talk a bit about public space. You work a lot with public space and with different types of audiences. So what is your approach to public space?

It again comes back to where you are and who you’re working with. In the role of city planner, I had responsibility for developing all the public spaces in the whole city, which included marketplaces, waterfront, parks and streets. I also included the 40 courtyards of the city. I start by listening to the site quietly on my own- just feeling what the place is about and how it’s unique. Because I love nature, it might just be experiencing the sky. Then the sky becomes very important. Another place might be very windy. In Norway, there’s a lot of like windy places. It could be the spatial qualities of the buildings around you and what cultural era they come from. Or vegetation that has survived, or the seeds under the asphalt. If we just take the asphalt away, the world of insects is revealed. The urban birds love that. The people who are also living there, what they want and intend. So that’s kind of how I start, I guess. The rest evolves from gradually understanding the place.

Uh, So what is the concept of public space for you? If you work with public and private space, we use different strategies.

Yes….

So what does it mean for you if you work with public space versus private spaces?

That’s an excellent question. I think when it’s a public space, it must be accessible to everyone. You can have a private cafe that has outdoor service as long as there’s also a space for people to sit without ordering food. The space is free, and everybody can enjoy it collectively. Public staff caretakes and cleans it. They also caretake the ecological values.

And what do you think? How can artists and creatives change their public spaces?

I think that today most planners, at least in Norway, have education regarding the infrastructure of a city. But often there’s a whole range of needs that are forgotten, having to do with intuitive thinking and feelings…. emotions, experiences, imagination, and values. Since the meaning of the place changes over time, artists can combine layers in new ways. They can reinterpret what the city could be. So, I think that artists are extremely important. Local artists have rooted in place identity. Often, they have studios or are connected to an art hall nearby; they explore their spaces in innovative ways. Engineers, architects, and city planners have concepts about physical needs: buildings outdoor seating, transport, etc. The content and human scale is missing…. like who’s going to be using it? What kind of events, happenings, shops, family functions? Are we going to be farming here? Or playing with robotics? Are there trees and views? How do sensitive creative individuals experience the place? Can you actively join in making the content? I think artists are key stakeholders.

So do you think that artists and creatives should be involved in city planning?

Oh definitely and I have involved artists and creative people and every project that I’ve done now and it makes such a huge difference. Because you know, it’s about values. Artists are very good at interpreting the unique character of the site and talking to the people who live and work there.

In your project, you involve different types of stakeholders. You work either with people with dementia or people from public space or with the kids from schools. So what are your strategies to include the different voices, different needs and interests?

Because I’ve chosen to work with projects that I find meaningful, there is usually an aspect of social change, listening to people whose voices aren’t heard. Umm, like in the project that I’m working on right now with artist Greta Rokstad. I’ll just use the example of the garden for those with dementia. We started the project with a friend whose mother was placed in a care facility. While visiting, we realized that none of the people in the building were allowed outside because they lacked the staff to accompany them. Maybe they would get lost? Many had been farmers their whole life and were now shut in. We decided to make a garden that would be safe for them and also involve the dement residents in the actual planning. So we did an hour of interview with each to chat about their interests and how they felt about gardens. The garden is finished now, and most of us have been working for free. The residents are outdoors quite a bit on their own. The greenhouse is built with leftover windows of the families. Then we realized that many of the residents weren’t able to farm because they were getting a little bit too old. Now the daycare next door visits to help grow vegetables. The residents chat with kids.

So is the Garden accessible for all inhabitants?

It is, but it’s zoned, so we have the greenhouse areas open for everyone. But we also have an area around closer to the living room that is private. They don’t have to talk to anybody if they don’t want to. So we’ve zoned it into three different areas, the most private, the family area and the neighborhood gathering spot. The gathering spot will invite not only the neighborhood, but visitors to do different projects. Many of the larger care homes are huge, hospital-like places with lots of tall buildings and they don’t always have enough sunshine or enough nature. Maybe this project can change how we take care of our elderly and sick, including them in our daily lives again.

Nice. Is it still an ongoing project?

Right? Yes, we’ve done the 1st and 2nd phases and are working on the last most public space. We are putting in a fruit orchard and campfire pit for the daycare center and neighbors.

Uh, let’s talk about urban ecosystems.

Yes….

Let’s talk about your view on urban farming or urban agriculture. How does it work? What’s the concept?

Urban space Lab just won the bid for a feasibility study for our region. Last week we had our first workshop with 20 different urban farming initiatives. The first question we asked was “what is urban in Norway”? Because I think urban can mean so many different things depending on what place you’re in. With two larger cities, many medium-sized towns, and a lot of smaller villages the term ‘urban’ may more nuanced. We’re very interested in the geographical setting for urban initiatives. In Norway, there’s a lot of beautiful nature and farmland surrounding the cities. Are you growing food in the higher mountains or in the coastal archipelago? And how does that affect the way that we look at urban farming in the region? We have found that lots of people work for free. They’re doing urban farming because they love growing and want to make a difference where they live. Many teach children how to grow things. Or how to establish new ecosystems in our industrial region.

Wetlands are very relevant – with birdlife, insects, and animal shelter. Water farming and floating gardens. Permaculture techniques and fruit forests are also interesting. And if you can reuse plants and food waste as compost, that’s circular, so there’s so many different aspects. Roof gardening local food. Pollinator corridors. On the island where I live we have 60,000 bees and 5 beekeepers. We planted 80 fruit trees at our school, and we have an outdoor kitchen. So I think that every community has a different way of looking at farming.

Tell us a little bit about your current career change from landscape architect to becoming an artist.

I’ve been a landscape architect for 38 years. After working with artists, I became inspired to actually become an artist myself. So, I’m in the master’s program at Leslie University in Boston. I’m starting to understand what it means to be an artist. The whole idea of environmental art is engendering experiments and I will soon be building a studio. Communicating with a 900-year-old oak tree that is really close to my house and listening to the whispering of the reeds is so satisfying. Filming burning jellyfish without burning my hand is a challenge.

And what was the main motivation for changing your career and studying again?

I felt that there was half of me that has been very repressed working in that logical world- the one we were talking about where the functional, physical aspects of development rule. I have a need to also express my feelings, my intuitions, and my imagination in projects, and I think that it will free me. To become a full person rather than just half of a person.

Thank you very much, Laurie. Thank you for your insights and a great story.

co-author of the article: Martin Mojžiš

Supported by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through the EEA and Norway Grants.

Working together for a green, competitive and inclusive Europe