She is over 100 years old, survived Auschwitz and still teaches. How to live according to Magda Zadorová

This is the story of a very strong lady from Košice – Magda Zadorová, born Sternová, has survived more than can be expressed in written words. This article describes her life in Czechoslovakia in the 1930s, in a Jewish ghetto during the war and in a brick factory in Košice before her deportation to the Auschwitz concentration camp and life in the post-war communist times. Above all, however, it is a statement about the determination of a person who, even in the most difficult situations, is able to make the most of his/her strongest attributes and get through something unthinkable.

Stay resilient

Magda Sternová was born on December 22, 1919 into a Jewish family in Košice as the eldest daughter in a family of six children. As a very young woman, she spoke several languages – since they spoke Hungarian and German at home, she studied Slovak, French, Latin at school and English during private lessons. The dream of studying languages at the Faculty of Arts in Prague, where she was accepted, was shattered due to the starting war and anti-Jewish restrictions. After the disintegration of Czechoslovakia and the Vienna Arbitration, Košice became part of Hungary and Magda’s family lost property, jewellery and money, and in 1944, they got imprisoned in the Košice ghetto. Due to the government of Miklós Horthy, transports to the concentration camps from what was then Hungary were delayed for about two years, which meant that a lot of lives were saved. During this period, Magda needed to maintain her inner strength and take care of her family.

“Everything is a matter of nature and whenever possible you have to choose the better option out of two. One must remain strong and resilient. I had to do everything I could to keep my family safe. My mother suffered in the ghetto and the war affected her to such an extent that she lost it. They took all of our property and radio, we had no connection to the outside world, no news. A few streets in Košice were closed off in which the ghetto was created and they kept us there for about four weeks. They sent a family of six from the Hungarian border area to our three-room apartment with eight family members, and we had to learn how to live together. We helped each other, we didn’t argue and did not cause any unnecessary conflicts. Every day there was a list of things and tasks to be done, we always had some sort of schedule. We didn’t know what would happen to us – I was very young at the time and I was angry with the man who had warned us about avoiding the brick factory. There, together with more than 10,000 other Jews, we stayed in very poor living conditions. From there they sent us straight to Auschwitz.”

Life is no picnic

Out of the eight members of the family, only four sisters survived the concentration camp. A few years before the transport, Magda married Andrej Zador, who was later dragged to labour camps in Russia and who she would not see for the next four years. After the war, as one of the very few, he returned to the city and found Magda so that they could start living again.

“Life is no picnic. Although it’s easier said than done, you have to stay optimistic. Without that, I could never have survived the war and the camp. My husband and I had our only son after the war, and all my sisters got married and moved to Israel, where we also planned to go. In 1968 the Russian occupation took place, the borders were closed and we could not go anywhere. My son left for America and today, he is a renowned scientist in prenatal fetal research – thanks to his work, he was invited for a private visit with the Pope.

I worked at the Scientific Library in Košice and since I spoke so many languages, I spent years taking care of international correspondence and communication thanks to the knowledge I acquired as a high school student. This included, for example, communication with libraries in the German Democratic Republic, Hungary, but also The Library of Congress in Washington, which is the largest library in the world. Languages were what kept me going and what gave direction to my life. When I retired, I immediately started teaching privately. I am still doing it till this day.”

Keep smiling and study

It was the education and ability to speak more than five languages which greatly influenced Magda’s journey. According to her, the most important thing for any generation is to study, learn languages and think optimistically.

“Americans often repeat the saying ‘Keep smiling’, and it is indeed true. It feels very different to be with someone who is positive. I have not done any miracles in my life, but I have always focused on being strong and healthy. It is also important to develop critical thinking and read relevant literature – I was not a member of any association and I did not allow myself to be influenced by ideologies. As a 16-year-old, I read Tolstoy and Dostoevsky without knowing the context of the philosophy of their time. Although these were very interesting to read, I was not mature enough to understand them yet and I had no one to guide me.

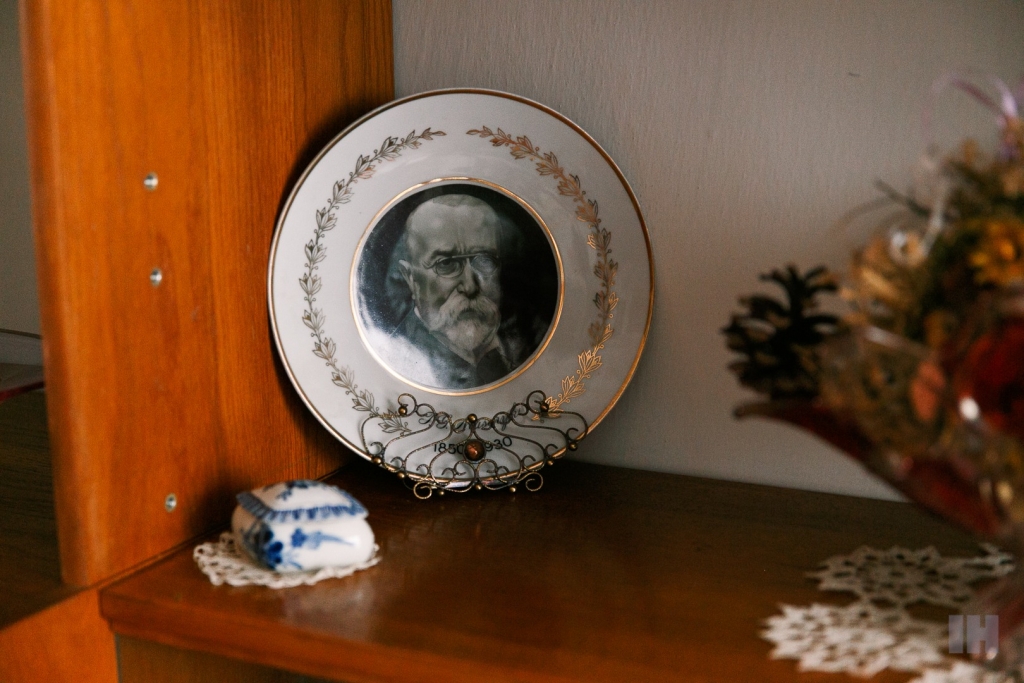

I believe that education affects us immensely throughout our lives. As I belonged to the last students who graduated before the war, I took the school very seriously with my classmates, which seems very different from what I see today. For example, when we were told that T. G. Masaryk died, we cried as if our real father had died. We loved him.”

“It’s hard to explain to young people that they should learn from the past that happened to us – they don’t own that past, they didn’t survive what we had gone through. But what happens when there are only memories of the survivors and their authentic description? It is terrible to see how the fascist parties came to power and are represented in the government, to have such strong support. I, therefore, address young people to be careful because history can repeat itself.”

Lifelong mission

What is the secret to a meaningful life? The 100-year-old language teacher claims that the biggest mistake we can make is to nurture laziness and spend time on useless activities. According to Magda, one tip for that is to have a precise schedule and activities planned constantly.

“You always have to do something useful. The most important thing is to have a mission, a goal – to know why we get out of bed in the morning. I have a strict regime for every day and I don’t indulge in lying in bed more than what is necessary – I take care of myself, shower, have a good meal and teach about two lessons a day. They often tell me that I look much younger than I actually am. I look younger because I have to. If I started to feel sorry for myself, everything would wither away. I currently teach English and German language to about seven students. I only teach adults who have their own families and responsibilities – if they cancel a lesson from time to time, I am just as happy as students in regular schools. The same goes for the holidays, that is when I am ‘frei’.

How could I enjoy my free time if I hadn’t done anything my whole life? I’ve been teaching ever since I retired, and to be honest, I probably wouldn’t go to a hundred-years old teacher myself. Having said that, I still get new offers, but I don’t accept new students anymore. After so many years of work, I choose who I will pay attention to. I don’t have patience when I see that someone doesn’t have talent. But the important thing is not to stop working.”

Live for the present moment

Last summer, a monument at the Košice brick factory on Idanská Street was unveiled, the very site where Magda Zadorová and her family and thousands of other Jews were placed before their deportation to the concentration camp. Magda, as the only remaining survivor from that era, gave an authentic description of what was happening in the brickyard in 1944.

“When I was at school, we translated philosophical texts by Virgil, Ovid and Seneca in Latin. Even after so many years, the motto Carpe diem quam minimum credula postero is still on my mind – Seize the day, put very little trust in tomorrow. We live for the moment, the present, nothing else. When I finished my speech at the memorial, Milan Kolcun was standing next to me. He invited me to his talk show Bez šepkára in The State Theatre of Košice to tell the audience what had happened to me in my life. It’s hard to explain to young people that they should learn from the past that happened to us – they don’t own that past, they didn’t survive what we had gone through. But what happens when there are only memories of the survivors and their authentic description?

It is terrible to see how the fascist parties came to power and are represented in the government, to have such strong support. We are at the same place we were 70 years ago when the fascists started to show up little by little. Even in my worst nightmare, I would never have believed that after the butchery I’ve witnessed in my life, it would happen again. It’s not any different, it’s the same. I, therefore, address young people to be careful because history can repeat itself.”

Košice then and now

Magda Zadorová is a real Košice resident – she considers the city, where she has lived almost her entire life, a birthplace that she loves very much and has witnessed its development and growth over the last hundred years. She observes the city, almost 4 times more populated than during the war when it had 60,000 inhabitants, from the window of her apartment near the Old Town Hall. She claims that it is now almost unrecognizable from its Czechoslovak version in the 1930s, and she also remembers the moment when the first stone fell on the ground of Nové Mesto (New City) when the Terasa neighbourhood was being built. The descendants of her sisters, who managed to emigrate to Israel before Communism, visit her every year, they speak Slovak and Hungarian and consider Košice their second home. They maintain their patriotism to the city even from a great distance.

“My sisters’ children and their children adore Main Street, which creates the impression of a spa town. We always go to the theatre for ballet or opera, we look at the Art Nouveau houses of the original Košice, we go for dinner to Baránok and walk around the Bankov area. I do not have memories of this city – I have had my whole life in it. But a city without a family doesn’t mean much.”