Two people, two continents. They are united by the city in which they decided to live and work. Foreigners in Košice – Part 1

They live among us, but we know almost nothing about them. Foreigners. At times invisible, and yet their life story can be an unexpected source of inspiration for us. Košice has always been a multicultural city, where different nationalities met, and their mutual interaction significantly enriched the local culture. It is no different today. That is why we have decided to introduce you to the exciting stories of people from other parts of the world in a series of articles. How do they perceive our city, and why did they decide to live and work here?

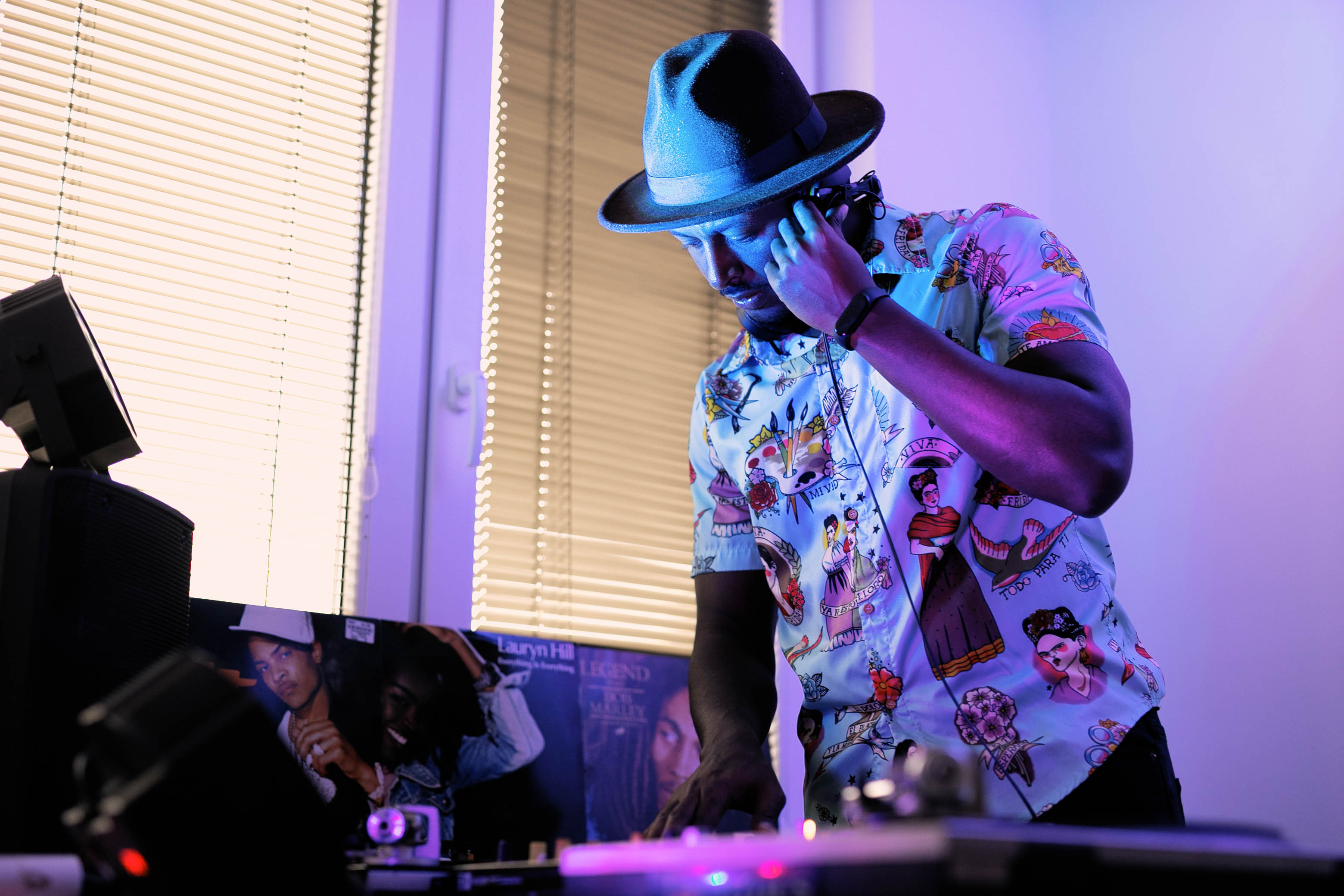

Košice has a huge potential in music, says jazz DJ Mikias

“I remember arriving in Košice and traveling from the airport well. It was the beginning of August 1994. I could smell summer in the air, and I was surprised that the sun was still shining even though we arrived at 10 pm. I didn’t understand what was going on; I had never experienced something like that before. There is a constant equinox in Ethiopia. The sun shines the same all year round, 12 hours during the day and night. And in the morning, I heard strange noises; I thought planes were landing. Only then did I find out that it was the sound of humming trams. We didn’t have them in Addis Ababa then. Now, of course, it’s different; the city already has an overground subway. From my first walk in the city center, I still remember the Fountain of Signs, and I was surprised that very few people were on the streets. Addis Ababa was much bigger and overcrowded with people.”

Mikias was ten years old when they moved from Ethiopia to Košice. His father had previously studied here for six years at the University of Veterinary Medicine. He became a veterinarian and returned to Africa. There was no indication that he was eventually going to move back to Košice with his family. Everything was changed by the conflict that broke out in the country. “When I was 7, we experienced a war. After the lost elections, the previous government (the Mengistu Regime) did not want to give up power, so the resistance troops invaded the city. We heard gunfire, our neighbor died. It was tragic. Few can imagine what it’s like to live in a country where conflict suddenly breaks out. My father decided that we would go back to Košice.”

A month after arriving in Slovakia, Mikias started primary school. “My father taught us the Slovak language every day. We had a big board at home. He kept writing new words on it. At school, I had a nice teacher who seated me next to the best student in the class to help me integrate.” However, while getting acquainted with the Slovak reality, he quickly encountered discrimination. “It was not pleasant. I first encountered racism here in Slovakia. There is no such thing in Ethiopia. I didn’t understand it for a long time. I shut myself off from the outside world then and didn’t believe in myself. It wasn’t until later that I overcame it.”

He gradually fell in love with the city, and even though his siblings and mother now live in Canada, he stayed here and started a family. “Life here is good, peaceful, and safe. I can no longer imagine living somewhere else. Košice is my city.” In addition to working in the IT field, his passion is music, DJ, and that connected him with Košice. He has been passionate about it for more than 15 years and believes that music is a communication channel that can influence people. According to him, the DJ is responsible for the mood of the audience. Therefore, he must empathize with people and react to their needs. “We evoke different feelings through music, and my aim is to create positive energy.”

Mikias specializes in hip-hop, rap, and jazz. According to him, Košice and the Eastern part of the country have great potential thanks to the creative people who live here. Although the mecca of his musical genre is Bratislava, he feels that change is also taking place in the metropolis of the East. “It helped a lot that Košice became the European Capital of Culture. To this day, the Use the City festival is organized, during which musicians can create music in various parts of the city. Then there is the White Night, and I always look forward to what I will experience. So the culture in Košice is moving forward, and that’s good.”

Days of the City of Košice could take place in other neighborhoods

The city is also tied with various festivals and regular cultural events, which should not be intended only for tourists. On the contrary, according to Mikias, everything is concentrated in the historic city center to the detriment of things. It could be different. “I lack more support for local artists, musicians who are based in non-central neighborhoods. Events such as Days of the City of Košice could be extended to other places outside the center. It is necessary to do something in these places and involve people from the periphery. Culture is ideal for attracting people and celebrating their city.”

Mikias would like the international Red Bull DJ festival to take place in Košice. He took part in it in Krakow and believes that such an event, as in Poland, could arouse the general public’s interest and tourists from the surrounding countries. Unfortunately, during the pandemic, the club scene closed to all DJs. Therefore, the future of nightclubs is still very uncertain. Nevertheless, Mikias is looking forward to returning to his favorite Blue Bell bar in the city center after the pandemic. He will once again make the evening more pleasant for everyone present with his Chillhop music.

People said that nothing could be done about it. I didn’t want to believe it, says Antoine about Luník IX

We follow the Belgian Antoine to the infamous neighborhood. He works for the Slovak organization ETP Slovakia, which uses the premises of the local community center for its activities with Roma youth. We meet an energetic man with a spark in his eyes and a friendly look. He radiates positivity. He will immediately take us for a short walk around the neighborhood. We walk around the first apartment building, and I notice the black walls on the balconies. I wonder why. “It’s simple; they don’t have gas. They burn wood in metal chimneys to generate heat in the winter. The smoke goes out through the balcony, and that’s why it’s black. Few people know this, and they need an explanation.”

Gradually we get to the most famous part of the neighborhood, a series of apartment buildings, which for many years represented Luník IX. Antoine tells me that there were heaps of trash just below these balconies. We mention the iconic photograph, which remained in people’s memory and presented this neighborhood in a negative light. Today there is no more waste, the lawn is clean, and children are playing here. They jump around and dance to the music of the local DJ. He stands next to me with a giant speaker and loudly plays a catchy song from the Gypsy Kings. Positive energy is quickly transferred to us, and I don’t even know how, but we are all dancing together all of a sudden. Antoine explains to me that locals have big plans for this place. “We came up with a project together with young people, we discussed it with the mayor, and we want to turn this place into a small park. There will be swings, benches, lights. We already have cameras. No one will throw trash here anymore because children and neighbors will be sitting on the benches.”

Community center

Antoine leads us to a community center, where several children are learning geography. They do many activities for young people; they lead a journalism course, have formed a music band, and often tutor children even after school. About 20 children regularly go to the center, and many more join sports activities on the playground. I learn that Antoine is a trained surveyor and has lived in Slovakia alternately since 2007 when he received a job offer. I am quite naturally interested in how he got to his current job with the Roma community. “From time to time, the topic of Luník IX came up among my Slovak friends. It cannot be avoided. Very often, I have heard the opinion: ‘Nothing can be done about it. That’s just the way it is.’ I couldn’t believe it. I have argued that some progress can always be made, even if it is not easy. They kept telling me, ‘You’re not from here, you don’t know them, and you haven’t lived with them.’ So I called the center once that I’d like to help. They are always looking for mentors. First, I was going to Great Ida in the evenings, after work. Later I came to Luník. For about five years, I gradually became acquainted with this work. Since last year, I only work at the center,” says Antoine.

When asked what he likes most about this job, he answers: “I was satisfied in my previous job, but here I see a higher goal, and I am in contact with people. At least I can change something on the go.” He says that one of the problems is that in Roma education, the role of the Romani language is overlooked. “No one looks at the Romani language. No one has codified it, and no one is paying attention to it. There are only two schools in Košice where Romani is taught. That is not enough. Pupils learn grammar, reading, and writing, but other subjects are not taught in their mother tongue. What about math or geography? They study in Slovak schools but have not had a single course in Romani in their lives. They have no idea how to write in their language, what are the grammar rules. Many only speak ‘kitchen’ Romani.”

I feel better in Košice than in Brussels

When Antoine came to Košice, he found several friends at the French Institute, which organized activities for foreigners. However, he had to take care of everything else himself. In Belgium, he started learning Slovak to integrate into the local environment as quickly as possible. Today he speaks fluently.

According to him, people in Košice are very friendly and considerate to foreigners. There are a few things he likes about our city and why he decided to live here. “Košice is small, but at the same time big enough, which is important to me. I don’t like big cities. I also lived in Brussels, but I feel better in Košice; I’m not disconnected from the culture. If I want, I have it. For example, Tabačka, Kino Úsmev or Kulturpark.” He is sensitive to the changes that have taken place in the city in recent years due to the ECoC project. He is pleased that the city is gradually changing its approach to cycling, as it is his favorite mode of transport. “We are just getting started. Still, it’s progress. The way of thinking has changed, from ‘screw it, bikes are just a hindrance,’ we switched to ‘it would be good if we changed something.” Cycling is becoming popular even among Košice residents, but we can’t compare it to Copenhagen, maybe in ten to twenty years.”During the interview, he explains to me how his native Belgium approached changes in transport. “They purposefully reduced the number of cars in the city, reduced parking spots, and reduced lanes from two to one. This way, they created space for a wide cycle path or bus lane. As a result, cars are no longer a priority in the city,” concludes Antoine. At the same time, he picks several bicycles for the children from the community center, which they received as a gift from OZ OKOLO and the bicycle service. Something is always happening at Luník IX, and although it is far from an ideal situation, it’s nice to witness the sincere effort of people to change things for the better.