We didn’t have time or desire to make art.

The beginning of the invasion caught Ukrainian artists Mark and Maksym at a residency in Košice.

It is important not to continue with normal life

We’re sitting on the floor, softened by cushions in the atelier of the Košice Artist in Residence residency program. Surrounded by the bags of cement, bubble wrap, paper boxes, various sculpted objects, and those in the process of being formed. The room is inviting the light of an early afternoon inside, and the strong wind stays behind the windows of Šopa gallery as we’re starting to talk about the art and process behind the work of Maksym Khodak, a 20-years old artist from Kyiv. He usually works with topics of history, collective and individual memory, a critical rethinking of Soviet legacy and the current political situation, and together with fellow-artist Mark Chehodaiev, they spent two months on KAIR residency in Košice.

Did you already have a vivid idea of the project when you came here and stuck with it?

I had it. But then the war happened, and I kind of lost it. After a few days in Košice, I got sick with covid and was isolated for ten days (maybe I caught it already in Kyiv but got sick only after arrival). Then Mark and I finally started to work, and a few days after that, the war began. We’ve been sitting in our apartment, reading the news 24/7, trying to figure out what happened, and didn’t have the desire and time to do art.

Can you guide me a bit through that moment when you found out about the war…

My friend called me at 6 AM: “Wake up, the war has started, Ivano-Frankivsk was bombed.” Then I opened Facebook, started scrolling, and woke my residency partner Mark and told him what was happening. During the first hours of the strange vacuum, we were trying to understand what had just happened.

For two days, we didn’t have almost any sleep. We’ve got the live broadcast on video, calling with parents and friends, and checking Telegram messages.

How did the transformation of your initial project idea develop?

I had a feeling that I lost all my previous ideas, including my idea for Košice, because they seemed so irrelevant in this new light, “new world”. Reality is so powerful that any image you create cannot “beat” or overcome this reality. My initial idea was cobblestones with engraved logos of Soviet photo cameras related to ideological ideas of the Soviet Union. Because in my work, I often deal with the Soviet past.

Recently I started to think about the possible revolution that young people could lead. How they can build a new world on their post-soviet ruins. Moreover, Košice is also a medieval city with many cobblestones, built within the context of the Soviet past. I didn’t have that much free time for walking around the city, but during one of my first such walks, I saw this monument near Aupark dedicated to the Soviet army. Someone freshly painted it with yellow and blue, and I really like this transformation and think a lot about it. This interest led me a little to the final idea that I would present in Košice.

In the end, I created the pedestals from monuments with tanks, which you can find almost in all Ukrainian cities, but without the main artifact on them, in the form of “pokladnička” – moneybox. It has more layers and contexts why I do this. First of all, when the war started, artists started raising money with their art. It is a primary reflection of the condition of art in the circumstances of the war. This work has a lot of my thoughts about: what is art? For me, if we take an overall look at it, Art is the aestheticization of capital. Moneybox is precisely this.

About some forms of art, a viewer can immediately say or label them as politically engaged. Still, for some people, it will always be just a gesture because they may think that art and politics are isolated compartments. But even in your previous work, I noticed that you want to make art political not by some added meaning or added element, but you’ve interwoven it into the very core of art. Are people supposed to put money inside these money boxes?

Yes. I want to collect money in some sort of a tricky game. I propose raising money for Ukrainian art, and then the game “what is art” starts. Basically, you already donate to Ukrainian art because You put money inside the art. If you broke the moneybox to put out money, then the art ends/is destroyed because it was used as a functional thing. For me, one of the descriptions of art is the concept of a dysfunctional thing.

So if I want to make art more powerful, I must not break these sculptures. But it can look like a fraud for people who donate, that I keep money inside. But we must remember that when I don’t break the moneybox and sell it with the money inside, the value of this art is even bigger by the amount of capital inside. Therefore, people in Ukraine receive more money. And the art will not be destroyed.

And why do I do the pedestals for the monuments?

I read a story about how In 2014, in the Donbas region, Russian separatists stole the tank from the monument and used it in a war – they put the fuel inside the tank, which was in working conditions. So the tanks from monuments are going to war. History is literally “doing” the war. For me, this war is a “soviet past war”. In his propaganda speech, Putin mentions how he wants to resurrect the great Soviet past. So the empty pedestal from the monument dedicated to the victory in WW2 is a clear metaphor for the war happening now. And also, is the monument without a tank a monument, or is it just a pedestal? In art, a pedestal is not a sculpture. Is the pedestal only a function, or is it still art? Those are the possible questions and trajectories of my thinking.

You work a lot with collective and individual memory and Soviet legacy. In one of your projects, you deconstructed soviet-realist film into an abstract thing. In Ukraine, after the Dignity revolution there came this “decommunization law” that said that all Soviet monuments or other signs from this period should be removed from public space. And you said, about this process, that it’s not a healthy thing to do because trying to erase these important periods from your history can lead to kind of its recurrence.

For me, what’s happening now, it’s actually a recurrence. We shouldn’t destroy those monuments, we need to start “owning them”. Russians use these Soviet monuments and marks for their propaganda. Russia wants to occupy all the Soviet past, but that past is also ours. It’s also the past of other independent countries that were a part of the Union before. We need to critically rethink it and say it is also our part of culture.

If Youth try to dig deeper into this legacy and rethink what it has left in us, some members of the older generation can have different opinions on that – some are glad, and some may say you have nothing to do with it, you didn’t live in it.

I didn’t receive any negative reactions. It’s a tricky topic in Ukraine. It’s not banned, but it’s not appreciated. Everything with some left-wing ideas raises suspicions to be a “hand of the Kremlin.” If you say you’re left, some people in Ukraine tell you that you’re stupid because it reminds them of the repression that happened in the Soviet era. In Western Europe, modern left-wing ideas are usual, but in Ukraine, we have this trauma. So I was trying to think of how to make a left-colored revolution to build a better world in this post-soviet context. And how to use the power of “out of age” institutions for that.

And really, the Younger generation is more left-wing. If you take a look at TikTok, for example, young people promote some left ideas there, talking about climate change and explaining how capitalism is becoming more and more absurd every day.

It’s important to distinguish between different shades of the Left and different theories. Do you have many friends who are trying to make a “new Ukraine”? It almost sounds like a phrase, words too big, but I know how you meant it.

People in Ukraine are really politically conscious and active since, in the current context – you cannot actually be Not political. They think about a better world every day. And with the war situation, many of them just wait to receive a chance to literally rebuild a new Ukraine, which was destroyed.

I had some discussions with older artists who were saying that the new generation is more apolitical in comparison to them. In some ways, it is true. But I think young people just have struggles with how to move from theory to practice. I would like to give them the motivation to make a political gesture, to inspire them on how they can transform what they love into political action.

Can you imagine making apolitical art?

For me, apolitical art is nonsense. Art always exists in public spaces. Even if nobody sees it. And public space is literally a political space. Some of my artist friends deal in their work with their inner trauma and so on. It’s almost a trend now, but it’s so bizarre for me. Especially if thinking a little about money which is used to produce new works. Most often, we use the money of taxpayers. All the grants from government institutions are basically taxes.

It’s also my attempt to implement my theoretical system in practice. I struggle with the question of How to make political art capable of changing the world. And how art can be political by itself and not just to use art as a language to communicate political gestures.

In one of your works, you used limbs as a way of portraying a territory. Amputation of a limb equals an amputation of territory. Not only in Ukraine (Krym) but also in Moldova or Azerbaijan, all by Putin’s actions. Because amputation of an arm or a leg is a traumatic experience, we need to adapt to a new way of life, new feelings. You asked if life is possible without prosthetics or if there will be any phantom pains. Did you make an exhibition out of this project?

I work faster than I have exhibitions (laughter). I have a lot of work that hasn’t been shown anywhere. But yeah, this work was created in 2019, and I don’t want to say that it is prophetic in some way. This feeling of living without some parts of you was already in the air for five years. I just documented this feeling and proposed to start a conversation that can deal with these questions.

Was it important for you to engage people? Would you do it anyway without contact with a perceiver or a reader, or is this contact crucial for you, because at that moment, the moment of publication, it’s turning into and becoming a political act?

For me, a viewer isn’t that important, in a way. Almost all galleries after the invasion are now empty. Some are even destroyed, without walls. I try to reflect on this, doing art for empty gallery space. But I think a lot about the conditions of art spaces in Ukraine, even before the war. Because I had a feeling for a while that nobody cared about the art.

I don’t look at art as a job. But it doesn’t mean that I didn’t care about working conditions. I just try to think better. You don’t receive a lot of honorarium in Ukraine for it, so it doesn’t really make a difference if you show it in a gallery space or do it for yourself. Now I think of how art can be political even if nobody sees it. How can it be a force to imply a change? I want to ruin this usual logic for political art: art — viewer —viewer creating a political gesture.

So if it’s possible to skip the viewer and maybe directly change some law?

I hope so. At least I try to propose some theory that can help imagine it.

In your previous work, you dealt with propaganda, consumerism, a heritage of industrialization, and what damage it has left in the context of climate change. Also, you worked with children when you held the drawing competition where they should draw their favourite oligarch. Rethinking the function of oligarchs in Ukraine. Many of them are also known for funding education, art exhibitions, and are sometimes seen as good philanthropists.

This project reflects my experience as a child. I’ve always been involved in some strange competition organized by politicians or some private companies. Also, the fight against oligarchy has continued in Ukraine for many years. I’ve heard the same names of oligarchs again and again when I was growing up, and they still have power nowadays. So my project was simple. I organized a competition of children’s drawings with the topic “My favorite oligarch”. So basically, I was waiting for the children to draw a bunch of oligarchs, and they received prizes.

My strategy was that I didn’t say that I criticize oligarchs. I just said they were cool and only revealed my true intentions after the competition was finished.

I didn’t expect this project to become so scandalous in a way. I was a bit afraid when it became so viral in Ukraine. I received a lot of negative reactions from people – which is a good sign – that they didn’t appreciate the role of oligarchs in nowadays society. In the end, I received around 30 drawings from children around Ukraine. Winners received funny prizes – Monopoly, fake money, fake Rolex, miniature models of Mercedes, constructor in the form of oil pumps.

The sad thing is that oligarchs really do such competitions. When I was already working on a project, I discovered that some time ago, Rinat Akhmetov, the richest person in Ukraine, did the same project.

He called it a Big person with a big heart — meaning him. I discovered it only after I started developing my idea. I received some second-hand drawings that were drawn for his exhibition. Rinat, with a big human heart in his hands, appearing as some primeval god.

Did it bother you, all these negative and sometimes threatening reactions?

No, it didn’t. I was just tired and maybe a bit scared for a moment.

You also made an event with Mark called Ukrainian meme forces with the meme you saw.

I saw an article on NewYorker which called this war the first TikTok war. And TikTok is full of memes. Really if Ukrainians see an opportunity to transform some situation into memes, they do. And it’s total craziness, Russian soldiers are making TikTok in tanks, Ukrainians are making memes, a wounded girl in hospital, which Zelenskyj visited, told him happily We own TikTok now, everything is in Ukrainian!

Yes, we own TikTok, he told her. She was so happy.

What are your feelings before coming back to Ukraine?

I’m not returning yet, I’m going to Budapest for another residency, then to Zagreb for one small program, and then I feel that I will probably go to Ukraine. But I’m not sure. The war didn’t feel so real on a physical level, so it’s hard to say if I could live under continuing air strikes. Since it started, when we have been already here in Košice and saw it only from screens.

You have pictures on your phone next to the buildings that don’t exist anymore. They are not there anymore. You know it’s true, and this is reality, but you don’t have emotions. My brain locked my emotions to save myself. It’s important for me to return. I miss everything, and I should stay there. It’s important not to continue a normal life. This normalization is not helpful in this situation. The Kyiv region is free from troops, but the war has not ended yet, and there is still danger in return, airstrikes continue.

My own problems seem pretty small and not important for now. And my art too.

We’re moving to the exterior. It’s quite chilly outside, sunny, however, as we’re walking with Mark, with whom we have a completely different setting of talking and reflecting. In motion, heading to Kováčska street, photo shooting on Uršulínska meanwhile, trying the right pose for a photo and catching the convenient light, cars are passing, a mixture of sounds and noises and silences are entering our conversation. Disorder, Mark says calmly, with a gentle smile.

Mark (*1997, Kyiv), who also spent 2-months on residency in Košice, is a Ukrainian multimedia artist currently studying in Vienna, Austria. He’s interested in how the general context coexists with personal experience, and, in his often performative projects, he collaborates with other artists or spectators.

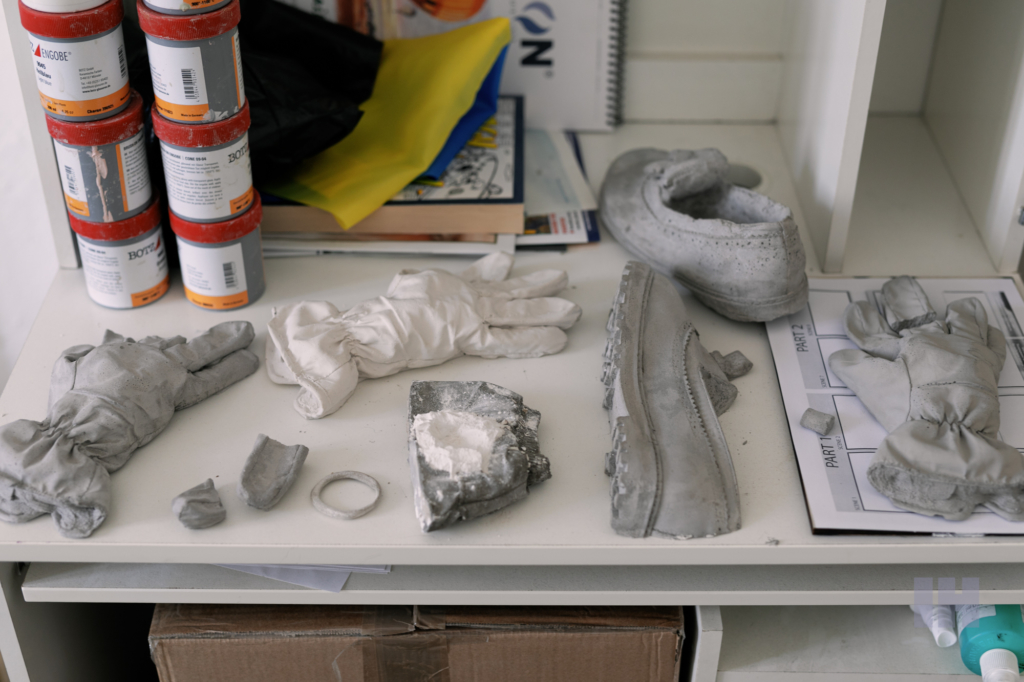

We’re on his way to place the objects he found on the streets, objects that someone lost — a glove, shoes, a hair tie. Not the original objects, but the replicas that he re-made from original ones into the form of a sculpture.

In your artistic practice, you work mainly with space and relationships in space, through which you develop your key themes of presence and memory. Can you tell me more about this project we’re right now literally moving towards its final phase?

“It draws the viewer’s attention to objects — things, clothes — lying on the streets of Košice. I’m working with the concept of loss and simulating a certain mechanism of memory preservation in the context of public space. Collecting found clothes/objects and afterward placing so-called monuments (size to size sculptures made out of concrete) at the same place where I found them.”

“Kvety? It sounds similar to Ukrainian.” Mark is pointing at the flower shop sign, reading it. Yes, it means flowers. We smile.

“What three words come to your mind about your residency in Košice? If you would close your eyes…”

“I would fall down.”

“So true.” I must agree as we continue to walk fast as we talk, but now we’re also laughing out loud.

“But one word that comes to my mind would be a disorder for sure. Definitely. Not only because of the current events. The disorder was part of my life even before. It totally also describes my personality. And personality then transforms into a way of working.”

And what are your feelings about the war and the fact that you’ve been here when it started?

I perceive the war through the screen and through a safe distance, through the phone calls and talks but not through the actions themselves. That’s why I’m still in the process of understanding my measure of being involved. That gradient, or a line, between spectator and participant. On the one hand, I’m a part of the context. I’m a Ukrainian citizen, and I’m proud of my country.

On the other hand, I didn’t have the same experience as people in conflict areas or who are running from danger or defending the country. My own problems and things seem pretty small and not important for now. And my art too.

It seems like such a defining moment – the place or context in which one is when something crucial is happening. But whether home or abroad at the moment, you go through something collectively…

Every Ukrainian deal with something at the moment, struggling to make the right decisions or conclusions. I think this fact is important to highlight. And I believe it works without exceptions. People in the armed forces, people who continue working in the factories, and those outside Ukraine organizing protests and actions…

They have the same goals because we are united as never before, and everyone is working for victory and spreading the truth. It is my impression, and it’s quite idealistic, I know. I can imagine that it should be more complex and probably not so clear, but I believe in it and don’t want to destroy that vision.

You went to Vienna yesterday because you’re studying at a site-specific department. Was this field of art something you developed and realized its significance to you during your studies in Kyiv?

I had an impression that a lot of my projects are site-specific. But the term and field itself it’s kind of not super stable for me, I mean, it is an extensive term, and it can include different approaches and things. But when I saw this faculty, I was surprised. I did not know that there could be a separate faculty for this.

At that time, I had already finished my Master’s Degree in Ukraine, so I had a lot of study experience in the wrong way. For my professors in Ukraine, the personal taste was really important, and making student works respond to their taste, was almost the only relevant base for that school.

In Angewandte (my Uni) kind of everything is possible. Everyone has their taste, but it shouldn’t be the only criteria, and it isn’t. Accepting different points of view. And I feel like I have this in Vienna.

We tend to change perceptions and feelings about our previous works differently, either towards being more critical or nostalgic about it or realizing completely new conclusions. Can you transport me to the time of the project that is dear to you even now, after some time?

It is actually not a project but just one photo that wakes up a lot of important memories for me right now. 12. 06. 2021. I invited all my friends to come to my room to say goodbye to it because I was moving out. I invited only people that were my guests in this room before (55-60 people). Came around 25 in general. I miss my friends, I miss my home, I miss a relatively peaceful time right now, pretty simple.

The Košice Artist in Residence programme was part of the event Matching Culture with Funding for future Slovak-Norwegian projects organised by Creative Industry Košice in collaboration with Urban Space Lab as part of the Slovak-Norwegian Cultural Matching initiative supported by Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway through the EEA and Norway Grants.

The event was attended by: Haidi H. Al-Juboori consultant of Vestfold and Telemark County Council, Joanna Magierecka Associate Professor of Drama and Theatre, University of South East Norway, Anna Mária Trávničková from Šopa Gallery and KAIR Košice Artist in Residence and Tor Erling Naas illustrator, writer, musician.